don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

XXXIII Sunday in Ordinary Time C [16 November 2025]

First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Malachi (3:19-20a)

When Malachi wrote these words around 450 BC, the people were discouraged: faith seemed to be dying out, even among the priests of Jerusalem, who now celebrated worship in a superficial manner. Everyone asked themselves: 'What is God doing? Has he forgotten us? Life is unfair! The wicked succeed in everything, so what is the point of being the chosen people and observing the commandments? Where is God's justice?" The prophet then fulfils his task: to reawaken faith and inner energy. He rebukes priests and lay people, but above all he proclaims that God is just and that his plan of justice is advancing irresistibly. "Behold, the day of the Lord is coming": history is not a repeating cycle, but is moving towards fulfilment. For those who believe, this is a truth of faith: the day of the Lord is coming. Depending on the image that each person has of God, this coming can be frightening or arouse ardent expectation. But for those who recognise that God is Father, the day of the Lord is good news, a day of love and light. Malachi uses the image of the sun: "Behold, the day of the Lord is coming, burning like an oven." This is not a threat! At the beginning of the book, God says, "I love you" (Malachi 1:2) and "I am Father" (Malachi 1:6). The "furnace" is not punishment, but a symbol of God's burning love. Just as the disciples of Emmaus felt their hearts burning within them, so those who encounter God are enveloped in the warmth of his love. The 'sun of righteousness' is therefore a fire of love: on the day we encounter God, we will be immersed in this burning ocean of mercy. God cannot help but love, especially all that is poor, naked and defenceless. This is the very meaning of mercy: a heart that bends over misery. Malachi also speaks of judgement. The sun, in fact, can burn or heal: it is ambivalent. In the same way, the 'Sun of God' reveals everything, illuminating without leaving any shadows: no lie or hypocrisy can hide from its light. God's judgement is not destruction, but revelation and purification. The sun will 'burn' the arrogant and the wicked, but it will 'heal' those who fear his name. Arrogance and closed hearts will be consumed like straw; humility and faith will be transfigured. Pride and humility, selfishness and love coexist in each of us. God's judgement will take place within us: what is 'straw' will burn, what is 'good seed' will sprout in God's sun. It will be a process of inner purification, until the image and likeness of God shines within us. Malachi also uses two other images: that of the smelter, who purifies gold not to destroy it, but to make it shine in all its beauty; and that of the bleacher, who does not ruin the garment, but makes it shine. Thus, God's judgement is a work of light: everything that is love, service and mercy will be exalted; everything that is not love will disappear. In the end, only what reflects the face of God will remain. The historical context helps us to understand this text: Israel is experiencing a crisis of faith and hope after the exile; the priests are lukewarm and the people are disillusioned. The prophet's message: God is neither absent nor unjust. His 'day' will come: it is the moment when his justice and love will be fully manifested. The central image is the Sun of Justice, symbol of God's purifying love. Like the sun, divine love burns and heals, consumes evil and makes good flourish. In each of us, God does not condemn, but transforms everything into salvation by discerning what glorifies love and dissolves pride. Fire, the sun, the smelter and the bleacher indicate the purification that leads to the original beauty of man created in the image of God. Finally, there is nothing to fear: for those who believe, the day of the Lord reveals love. "The sun of righteousness shall rise with healing in its wings" (Malachi 3:20).

Responsorial Psalm (97/98:5-6, 7-8, 9)

This psalm transports us ideally to the end of time, when all creation, renewed, joyfully acclaims the coming of the Kingdom of God. The text speaks of the sea and its riches, the world and its inhabitants, the rivers and the mountains: all creation is involved. St Paul, in his Letter to the Ephesians (1:9-10), reminds us that this is God's eternal plan: 'to bring all things in heaven and on earth together under one head, Christ'. God wants to reunite everything, to create full communion between the cosmos and creatures, to establish universal harmony. In the psalm, this harmony is already sung as accomplished: the sea roars, the rivers clap their hands, the mountains rejoice. It is God's dream, already announced by the prophet Isaiah (11:6-9): 'The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, the leopard shall lie down with the kid... no one shall do evil or destruction on all my holy mountain'. But the reality is very different: man knows the dangers of the sea, conflicts with nature and with his fellow men. Creation is marked by struggle and disharmony. However, biblical faith knows that the day will come when the dream will become reality, because it is God's own plan. The role of prophets, such as Isaiah, is to revive the hope of this messianic Kingdom of justice and faithfulness. The Psalms also tirelessly repeat the reasons for this hope: Psalm 97(98) sings of the Kingdom of God as the restoration of order and universal peace. After so many unjust kings, a Kingdom of justice and righteousness is awaited. The people sing as if everything were already accomplished: "Sing hymns to the Lord who comes to judge the earth... and the peoples with righteousness." At the beginning of the psalm, the wonders of the past are recalled—the exodus from Egypt, God's faithfulness in the history of Israel—but now it is proclaimed that God is coming: his Kingdom is certain, even if not yet fully visible. The experience of the past becomes a guarantee of the future: God has already shown his faithfulness, and this allows the believer to joyfully anticipate the coming of the Kingdom. As Psalm 89(90) says: "A thousand years in your sight are like yesterday." And Saint Peter (2 Pt 3:8-9) reminds us that God does not delay his promise, but waits for the conversion of all. This psalm therefore echoes the promises of the prophet Malachi: "The sun of righteousness shall rise with healing in its wings" (Mal 3:20). The singers of this psalm are the poor of the Lord, those who await the coming of Christ as light and warmth. Once it was only Israel that sang: "Acclaim the Lord, all the earth, acclaim your king!" But in the last days, all creation will join in this song of victory, no longer just the chosen people. In Hebrew, the verb "to acclaim" evokes the cry of triumph of the victor on the battlefield ("teru'ah"). But in the new world, this cry will no longer be one of war, but of joy and salvation, because — as Isaiah says (51:8): "My righteousness shall endure forever, my salvation from generation to generation." Jesus teaches us to pray, "Thy Kingdom come," which is the fulfilment of God's eternal dream: universal reconciliation and communion, in which all creation will sing in unison the justice and peace of its Lord.

Second Reading from the Second Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Thessalonians (3:7-12)

Saint Paul writes: "If anyone does not want to work, let him not eat" (2 Thessalonians 3:10). Today, this phrase cannot be repeated literally, because it does not refer to the unemployed of good will of our time, but to a completely different situation. Paul is not talking about those who cannot work, but those who do not want to work, taking advantage of the expectation of the imminent coming of the Lord to live in idleness. In Paul's world, there was no shortage of work. When he arrived in Corinth, he easily found employment with Priscilla and Aquila, who were in the same trade as him: tentmakers (Acts 18:1-3). His manual labour, weaving goat hair cloth, a skill he had learned in Tarsus in Cilicia, was tiring and not very profitable, but it allowed him not to be a burden to anyone: 'In toil and hardship, night and day we worked so as not to be a burden to anyone' (2 Thessalonians 3:8). This continuous work, supported also by the financial help of the Philippians, became for Paul a living testimony against the idleness of those who, convinced of the imminent return of Christ, had abandoned all commitment. His phrase 'if anyone does not want to work, let him not eat' is not a personal invention, but a common rabbinical saying, an expression of ancient wisdom that combined faith and concrete responsibility. The first reason Paul gives is respect for others: not taking advantage of the community, not living at the expense of others. Faith in the coming of the Kingdom must not become a pretext for passivity. On the contrary, waiting for the Kingdom translates into active and supportive commitment: Christians collaborate in the construction of the new world with their own hands, their own intelligence, their own dedication. Paul implicitly recalls the mandate of Genesis: 'Subdue the earth and subjugate it' (Gen 1:28), which does not mean exploiting it, but taking part in God's plan, transforming the earth into a place of justice and love, a foretaste of his Kingdom. The Kingdom is not born outside the world, but grows within history, through the collaboration of human beings. As Father Aimé Duval sings: "Your heaven will be made on earth with your arms." And as Khalil Gibran writes in The Prophet: "When you work, you realise a part of the dream of the earth... Work is love made visible." In this perspective, every gesture of love, care and service, even if unpaid, is a participation in the building of the Kingdom of God. To work, to create, to serve, is to collaborate with the Creator. Saint Peter reminds us: “With the Lord, one day is like a thousand years and a thousand years like one day... He is not slow in keeping his promise, but he is patient, wanting everyone to come to repentance” (2 Peter 3:8-9). This means that the time of waiting is not empty, but a time entrusted to our responsibility. Every act of justice, every good work, every gesture of love hastens the coming of the Kingdom. Therefore, the text concludes, if we truly desire the Kingdom of God to come sooner, we have not a minute to lose. Here is a small spiritual summary: Idleness is not simply a lack of work, but a renunciation of collaboration with God. Work, in whatever form, is part of the divine dream: to make the earth a place of communion and justice. Waiting for the Kingdom does not mean escaping from the world, but committing ourselves to transforming it. Every gesture of love is a stone laid for the Kingdom to come. Those who work with a pure heart hasten the dawn of the 'Sun of Justice' promised by the prophets.

From the Gospel according to Luke (21:5-19)

'Not a hair of your head will be lost.' This is prophetic language, not literal. We see every day that hair is indeed lost! This shows that Jesus' words are not to be taken literally, but as symbolic language. Jesus, like the prophets before him, does not make predictions about the future: he preaches. He does not announce chronicles of events, but keys of faith to interpret history. His discourse on the end of the Temple should also be understood in this way: it is not a horoscope of the apocalypse, but a teaching on how to live the present with faith, especially when everything seems to be falling apart. The message is clear: 'Whatever happens... do not be afraid!' Jesus invites us not to base our lives on what is passing. The Temple of Jerusalem, restored by Herod and covered with gold, was splendid, but destined to collapse. Every earthly reality, even the most sacred or solid, is temporary. True stability does not lie in stones, but in God. Jesus does not offer details about the 'when' or 'how' of the Kingdom; he shifts the question: 'Be careful not to be deceived...'. We do not need to know the calendar of the future, but to live the present in faithfulness. Jesus warns his disciples: "Before all this, they will persecute you, they will drag you before kings and governors because of my Name." Luke, who writes after years of persecution, knows well how true this is: from Stephen to James, from Peter to Paul, to many others. But even in persecution, Jesus promises: "I will give you a word and wisdom that no one will be able to resist." This does not mean that Christians will be spared death — "they will kill some of you" — but that no violence can destroy what you are in God: "Not a hair of your head will be lost." It is a way of saying: your life is kept safe in the hands of the Father. Even through death, you remain alive in God's life. Jesus twice uses the expression "for my Name's sake." In Hebrew, "The Name" refers to God himself: to say "for the Name's sake" is to say "for God's sake." Thus Jesus reveals his own divinity: to suffer for his Name is to participate in the mystery of his love. In the Acts of the Apostles, Saint Luke shows Peter and John who, after being flogged, "went away rejoicing because they had been counted worthy of suffering for the Name of Jesus" (Acts 5:41). It is the same certainty that Saint Paul expresses in his Letter to the Romans: "Neither death nor life, nor any creature can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus" (Rom 8:38-39). Catastrophes, wars, epidemics — all these "shocks" of the world — must not take away our peace. The true sign of believers is the serenity that comes from trust. In the turmoil of the world, the calmness of God's children is already a testimony. Jesus sums it up in one word: "Take courage: I have overcome the world!" (Jn 16:33). And here is a spiritual synthesis: Jesus does not promise a life without trials, but a salvation stronger than death. Not even a hair...' means that no part of you is forgotten by God. Persecution does not destroy, but purifies faith. Nothing can separate us from the love of God: our security is the risen Christ. To believe is to remain steadfast, even when everything trembles.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole

Christ the King: «Today with Me in the Paradise». Love and vinegar

Dedication of the Basilica of St. John Lateran [9 November 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us! Let us be moved by Jesus' zeal for his Church, which he loves and wants to remain whole and faithful.

First Reading from the Book of Ezekiel (47:1-12)

Before rereading Ezekiel's vision, it is useful to recall the plan of the Temple that he knew, that of Solomon. Unlike our churches, the Temple was a large esplanade divided into courtyards: those of the pagans, of women and of men. The Temple itself had three parts: the open air with the altar of burnt offerings, the Vestibule, the Holy Place and the Holy of Holies. For Israel, the Temple was the centre of religious life: the only place of pilgrimage and sacrifice. Its destruction in 587 BC represented a total collapse, not only physical but also spiritual. The question was: would faith collapse with it? How could they survive after the destruction? Ezekiel, deported to Babylon in 597 BC, found himself on the banks of the Kebar River in Tel Aviv. During the twenty years of exile (ten before and ten after the destruction), he devoted all his energies to keeping the people's hope alive. He had to act on two fronts: to survive and to keep alive the hope of return. As a priest, he spoke mainly in terms of worship and visions, many of which concerned the Temple. Surviving meant understanding that the Temple was not the place of God's presence, but its sign. God was not among the ruins, but with his people on the Kebar. As Solomon said: 'The heavens themselves and the heavens of heavens cannot contain you! How much less this House that I have built!' (1 Kings 8:27). God is always in the midst of his people and does not abandon Israel: before, during and after the Temple, he is always in the midst of his people. Even in misfortune, faith deepens. The hope of return is firm because God is faithful and his promises remain valid. Ezekiel imagines the Temple of the future and describes abundant water flowing from the Temple towards the east, bringing life everywhere: the Dead Sea will no longer be dead, like the Paradise of Genesis (Genesis 1). This message tells his contemporaries: paradise is not behind us, but ahead of us; dreams of abundance and harmony will be realised. The reconstruction of the Temple, a few decades later, was perhaps the result of Ezekiel's stubborn hope. Perhaps in memory of Ezekiel and the hope he embodied, the capital of Israel is now called Tel Aviv, 'hill of spring'.

Responsorial Psalm 45/46

The liturgy of the Feast of Dedication offers only a division of Psalm 45/46, but it is useful to read it in its entirety. It is presented as a canticle of three stanzas separated by two refrains (vv. 8 and 12): 'The Lord of hosts is with us; our bulwark is the God of Jacob'. God, king of the world. First stanza: God's dominion over the cosmic elements (earth, sea, mountains). Second stanza: Jerusalem, "the city of God, the most holy dwelling place of the Most High" (v. 5). Third stanza: God's dominion over the nations and over the whole earth: "I rule the nations, I rule the earth". The refrain has a tone of victory and war: the Lord of the universe is with us.... The name 'Sabaoth' means 'Lord of hosts', a warrior title that at the beginning of biblical history referred to God as the head of the Israelite armies. Today it is interpreted as God of the universe, referring to the heavenly armies. The second verse is about the River. The evocation of a river in Jerusalem, which in reality does not exist, is surprising. The water supply was guaranteed by springs such as Gihon and Ain Roghel. The river is not real, but symbolic: it anticipates Ezekiel's prophecy of a miraculous river that will irrigate the entire region as far as the Dead Sea. Similarities can be found in Joel and Zechariah, where living waters flow from Jerusalem and bring life everywhere, showing God as king of all the earth. All the hyperbole in the Psalm anticipates the Day of God, the final victory over all the forces of evil. The warlike tone in the refrains and in the last verse ("Exalted among the nations, exalted on earth") means that God fights against war itself. The Kingdom of God will be established over the whole earth, over all peoples, and all wars will end. Jerusalem, the "City of Peace," symbolises this dream of harmony and prosperity. For some commentators, the River also represents the crowds that pass through Jerusalem during the great processions.

Second Reading from the First Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Corinthians (3:9...17)

The deepest desire of the Old Testament was that God would be forever present among his people, establishing a kingdom of peace and justice. Ezekiel expresses this with the prophetic name of Jerusalem: 'The Lord is there'. However, the fulfilment of this promise exceeds all expectations: God himself becomes man in Jesus of Nazareth, 'the Word who became flesh and dwelt among us'. St Paul, rereading the Old Testament, recognises that the whole history of salvation converges towards Christ, the eternal centre of God's plan. When the time is fulfilled, God manifests his presence no longer in a place (the Temple of Jerusalem), but in a person: Jesus Christ, and in those who, through Baptism, are united to him. The Gospels show this mystery of God's new presence in various ways: the Presentation in the Temple, the tearing of the veil at the moment of Jesus' death, the water flowing from his side (the new Temple from which life flows), and the purification of the Temple. All these signs indicate that in Christ, God dwells definitively among men. After the Resurrection, God's presence continues in his people: the Holy Spirit dwells in believers. Paul affirms this forcefully: "You are the temple of God, and the Spirit of God dwells in you." This reality has a twofold dimension: Ecclesial: the community of believers is the new temple of God, built on Christ, the cornerstone. Everything must be done for the common good and to be a living sign of God's presence in the world. Personal: every baptised person is a "temple of the Holy Spirit." The human body is a holy place where God dwells, and for this reason it must be respected and cared for. The new Temple is not a material building, but a living reality, constantly growing, 'a temple that expands without end', as Cardinal Daniélou said: humanity transformed by the Spirit. Finally, Paul warns: 'If anyone destroys God's temple, God will destroy him'. The dignity of the believer as the dwelling place of God is sacred and inviolable. Christ's promise to Peter is the guarantee: 'The powers of evil will not prevail against my Church'. In summary: God, who in the Old Testament dwelt in a temple of stone, in the New Testament dwells in Christ and, through the Spirit, in the hearts and community of believers. The Church and every Christian are today the living sign of God's presence in the world.

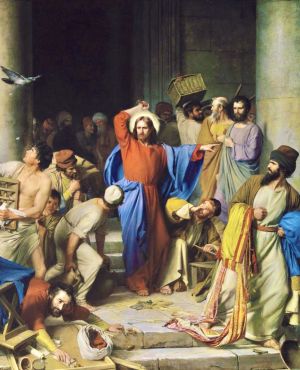

From the Gospel according to John (2:13-22)

Trade on the Temple esplanade. In the Gospel of John (chapter 2), Jesus performs one of his most powerful and symbolic acts: he drives the merchants out of the Temple in Jerusalem. The episode takes place at the beginning of his public mission and reveals the profound meaning of his presence in the world: Jesus is the new Temple of God. In Jesus' time, the presence of animal sellers and money changers around the Temple was a normal and necessary practice: pilgrims had to buy animals for sacrifices and exchange Roman money, which bore the emperor's image, for Jewish coins. The problem was not the activity itself, but the fact that the merchants had invaded the Temple esplanade, transforming the first courtyard – intended for prayer and reading the Word – into a place of commerce. Jesus reacted with prophetic force: 'Do not make the house of the Father a market'. He thus denounced the transformation of worship into economic interest and reaffirmed that one cannot serve two masters, God and money. His words echo those of the prophets: Jeremiah had denounced the Temple as a 'den of thieves' (Jer 7:11), and Zechariah had announced that, on the day of the Lord, 'there shall be no more merchants in the house of the Lord' (Zech 14:21). Jesus follows in this prophetic line and brings their words to fulfilment. Two attitudes emerge in response to Jesus' gesture: the disciples, who know him and have already seen his signs (as at Cana), understand the prophetic meaning of the gesture and recall Psalm 68(69): "Zeal for your house consumes me." John changes the tense of the verb ("will consume me") to announce Jesus' future passion, a sign of his total love for God and for humanity. His opponents ("the Jews" in John) react with mistrust and irony: they ask Jesus to justify his authority and refuse to be admonished by him. To their request for a sign, Jesus responds with mysterious words: "Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up." They think of the stone Temple, restored by Herod in forty-six years, a symbol of God's presence among the people. But Jesus is speaking of another temple: his body. Only after the resurrection do the disciples understand the meaning of his words: the true Temple, the sign of God's presence, is no longer a building, but the person of the risen Jesus himself, 'the stone rejected by the builders, which has become the cornerstone'. This episode, placed by John at the beginning of his Gospel, already announces the whole Christian mystery: Jesus is the new place of encounter with God, the living Temple where man finds salvation. The ancient cult is outdated: it is no longer a matter of offering material sacrifices, but of welcoming and following Christ, who offers himself for humanity. Faith divides: some (the disciples) welcome this newness and become children of God; others (the opponents) reject it and close themselves off to revelation. Jesus, by driving the merchants out of the Temple, reveals that the true house of God is not made of stones but of people united with Him. His risen body is the new Temple, the definitive sign of God's presence among men. The episode thus becomes a prophecy of Easter and an invitation to purify the heart, so that God's dwelling place may never become a place of interest, but remain a space of faith, communion and love.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole

Personal Sanctuary: Jesus expels the usurers from the Temple

Solemnity of All Saints [1 November 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin Mary protect us. The Solemnity of All Saints is an important occasion to reflect on our Christian vocation: through Baptism, we are all called to be 'blessed', that is, on the path towards the joy of eternal Love.

First Reading from the Book of Revelation of Saint John the Apostle (7:2-4, 9-14)

In Revelation, John recounts a mystical vision he received in Patmos, which is to be interpreted symbolically rather than literally. He sees an angel and an immense crowd, composed of two distinct groups: The 144,000 baptised, marked with the seal of the living God, represent the faithful believers, contemporaries of John, persecuted by the emperor Domitian. They are the servants of God, protected and consecrated, the baptised people who bear witness to their faith despite persecution. The innumerable crowd, from every nation, tribe, people and language, dressed in white, with palm branches in their hands and standing before the Throne and the Lamb, represents humanity saved thanks to the faith and sufferings of the baptised. Their standing position symbolises resurrection, their white robes purification, and their palm branches victory. The central message is that the suffering of the faithful brings about the salvation of others: the trials of the persecuted become a means of redemption for humanity, in continuity with the theme of the suffering servant of Isaiah and Zechariah. John uses symbolic and coded language, typical of the Apocalypse, to secretly communicate with persecuted believers and encourage them to persevere in their faith without being discovered by the Roman authorities. The text therefore invites perseverance: even if evil seems to triumph, the heavenly Father and Christ have already won, and the faithful, though small and oppressed, share in this victory. Baptism is thus perceived as a protective seal, comparable to the mark of Roman soldiers. This text, with its mystical and prophetic language, reveals that the victory of the poor and the little ones is not revenge, but a manifestation of God's triumph over the forces of evil, bringing salvation and hope to all humanity, thanks to the faithful perseverance of the righteous.

Responsorial Psalm (23/24)

This psalm takes us to the Temple of Jerusalem, a holy place built on high. A gigantic procession arrives at the gates of the Temple. Two alternating choirs sing in dialogue: 'Who shall ascend the mountain of the Lord? Who can stand in his holy place?" The biblical references in this psalm are Isaiah (chapter 33), which compares God to a consuming fire, asking who can bear to look upon him. The question is rhetorical: we cannot bear God on our own, but he draws near to man, and the psalm celebrates the discovery of the chosen people: God is holy and transcendent, but also always close to man. Today, this psalm resounds on All Saints' Day with the song of the angels inviting us to join in this symphony of praise to God: 'with all the angels of heaven, we want to sing to you'. The necessary condition for standing before God is well expressed here: only those with a pure heart, innocent hands, who do not offer their souls to idols. It is not a question of moral merit: the people are admitted when they have faith, that is, total trust in the one God, and decisively reject all forms of idolatry. Literally, 'he has not lifted his soul to empty gods', that is, he does not pray to idols, while raising one's eyes corresponds to praying and recognising God. The psalm insists on a pure heart and innocent hands. The heart is pure when it is totally turned towards God, without impurity, that is, without mixing the true and the false, God and idols. Hands are innocent when they have not offered sacrifices or prayed to false gods. The parallelism between heart and hands emphasises that inner purity and concrete physical action must go together. The psalm recalls the struggle of the prophets because Israel had to fight idolatry from the exodus from Egypt (golden calf) to the Exile and beyond, and the psalm reaffirms fidelity to the one God as a condition for standing before Him. "Behold, this is the generation that seeks your face, God of Jacob." Seeking God's face is an expression used for courtiers admitted into the king's presence and indicates that God is the only true King and that faithfulness to Him allows one to receive the blessing promised to the patriarchs. From this flow the concrete consequences of faithfulness: the man with a pure heart knows no hatred; the man with innocent hands does no evil; on the contrary, he obtains justice from God by living in accordance with the divine plan because every life has a mission and every true child of God has a positive impact on society. Also evident in this psalm is the connection to the Beatitudes of the Gospel: "Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness... Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God." "Behold, this is the generation that seeks him, that seeks your face, God of Jacob": is this not a simple definition of poverty of heart, a fundamental condition for entering the Kingdom of Heaven?

Second Reading from the First Letter of Saint John the Apostle (3:1-3)

"Beloved, see what great love the Father has given us": the urgency of opening our eyes. St John invites believers to "see", that is, to contemplate with the eyes of the heart, because the gaze of the heart is the key to faith. Indeed, the whole of human history is an education of the gaze. According to the prophets, the tragedy of man is precisely "having eyes and not seeing". What we need to learn to see is God’s love and “his plan of salvation” (cf. Eph 1:3-10) for humanity. The entire Bible insists on this: to see well is to recognise the face of God, while a distorted gaze leads to falsehood. The example of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden shows how sin arises from a distorted gaze. Humanity, listening to the serpent, loses sight of the tree of life and focuses its gaze on the forbidden tree: this is the beginning of inner disorder. The gaze becomes seduced, deceived, and when "their eyes were opened," humans did not see the promised divinity, but their nakedness, their poverty and fragility. In opposition to this deceived gaze, John invites us to look with our hearts into the truth: 'Beloved, see what great love the Father has given us'. God is not jealous of man — as the serpent had insinuated — but loves him and wants him as his son. John's entire message is summed up in this revelation: 'God is love'. True life consists in never doubting this love; knowing God, as Jesus says in John's Gospel (17:3), is eternal life. God's plan, revealed by John and Paul, is a "benevolent plan, a plan of salvation": to make humanity in Christ, the Son par excellence, of whom we are the members, one body. Through Baptism, we are grafted onto Christ and are truly children of God, clothed in Him. The Holy Spirit makes us recognise God as Father, placing in our hearts the filial prayer: 'Abba, Father!'. However, the world does not yet know God because it has not opened its eyes. Only those who believe can understand the truth of divine love; for others, it seems incomprehensible or even scandalous. It is up to believers to bear witness to this love with their words and their lives, so that non-believers may, in turn, open their eyes and recognise God as Father. At the end of time, when the Son of God appears, humanity will be transformed in his image: man will rediscover the pure gaze he had lost at the beginning. Thus resounds Christ's desire to the Samaritan woman (4:1-42): "If you knew the gift of God!" An ever-present invitation to open our eyes to recognise the love that saves.

From the Gospel according to Matthew (5:1-12a)

Jesus proclaims: "Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted": it is the gift of tears. This beatitude, seemingly paradoxical, does not exalt pain but transforms it into a path of grace and hope. Jesus, who always sought to heal and console, does not invite us to take pleasure in suffering, but encourages us not to be discouraged in trials and to remain faithful in our tears, because those who suffer are already on the way to the Kingdom. The term "blessed" in the original biblical text does not indicate good fortune, but a call to persevere: it means "on the march", "take courage, keep pace, walk". Tears, then, are not an evil to be endured, but can become a place of encounter with God. There are beneficial tears, such as those of Peter's repentance, where God's mercy is experienced, or those that arise from compassion for the suffering of others, a sign that the heart of stone is becoming a heart of flesh (Ezekiel 36:26). Even tears shed in the face of the harshness of the world participate in divine compassion: they announce that the messianic time has come, when the promised consolation becomes reality. The first beatitude, 'Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven', encompasses all the others and reveals their secret. Evangelical poverty is not material poverty, but openness of heart: the poor (anawim) are those who are not self-sufficient, who are neither proud nor self-reliant, but expect everything from God. They are the humble, the little ones, those who have "bent backs" before the Lord. As in the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector, only those who recognise their own poverty can receive salvation. The poor in spirit live in total trust in God, receive everything as a gift, and pray with simplicity: "Lord, have mercy." From this inner attitude spring all the other beatitudes: mercy, meekness, peace, thirst for justice — all are fruits of the Spirit, received and not conquered. To be poor in spirit means to believe that only God fills, and that true riches are not possessions, power or knowledge, but the presence of God in a humble heart. This is why Jesus proclaims a future and paradoxical happiness: "Blessed are the poor," that is, soon you will be envied, because God will fill your emptiness with his divine riches. The beatitudes, therefore, are not moral rules but good news: they announce that God's gaze is different from that of men. Where the world sees failure — poverty, tears, persecution — God sees the raw material of his Kingdom. Jesus teaches us to look at ourselves and others with the eyes of God, to discover the presence of the Kingdom where we would never have suspected it. True happiness therefore comes from a purified gaze and from accepted weakness, which become places of grace. Those who weep, those who are poor in spirit, those who seek justice and peace, already experience the promised consolation: the joy of children who know and feel loved by the Father. As Ezekiel reminds us, on the day of judgement, those who have wept over the evil in the world will be recognised (Ezekiel 9:4): their tears are therefore already a sign of the Kingdom to come.

- +Giovanni D'Ercole

Commemoration of All Souls [2 November 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us. After contemplating the glory of Heaven, today we commemorate the destiny of light that awaits us on the day of our earthly death.

1. The commemoration of All Souls' Day was set on 2 November only at the beginning of the 11th century, linking it to the solemnity of All Saints' Day. After all, the feast of 1 November could not fail to bring to mind the faithful departed, whom the Church remembers in her prayers every day. At every Mass, we pray first of all 'for all those who rest in Christ' (Eucharistic Prayer I), then the prayer is extended to 'all the departed, whose faith you alone know' (Eucharistic Prayer IV), to 'all those who have left this life' (Eucharistic Prayer II) and 'whose righteousness you alone know' (Eucharistic Prayer III). And to make this commemoration even more participatory, today three Holy Masses can be celebrated with a wide range of readings, which I will limit myself to indicating here: A. First Mass First Reading Job 19:1, 23-27; Psalm 26/27; Second Reading St Paul to the Romans 5:5-11; From the Gospel according to John 6:37-40; B. Second Mass: First Reading Isaiah 25:6-7-9; Psalm 24/25; Second Reading Romans 8:14-23; From the Gospel according to Matthew 25:31-46); C. Third Mass: First Reading Book of Wisdom 3:1-9; Psalm 41/42 2 $2/43; Second Reading Revelation 21:1-5, 6b-7; Gospel according to Matthew 5:1-12). Given the number of biblical readings, instead of providing a commentary on each biblical passage as I do every Sunday, I prefer to offer a reflection on the meaning and value of today's celebration, which has its origins in the long history of the Catholic Church. One need only read the biblical readings to begin to doubt that the term "dead" is the most appropriate for today's Commemoration. In fact, it is in the light of Easter and in the mercy of the Lord that we are invited to meditate and pray on this day for all those who have gone before us. They have already been called to live in the light of divine life, and we too, marked with the seal of faith, will one day follow them. The Apostle Paul writes, 'We do not want you, brothers and sisters, to be ignorant about those who sleep in the Lord, so that you may not grieve as those who have no hope' (1 Thessalonians 4:13-14). Saints, when possible, are not remembered on the anniversary of their birth but are celebrated on the day of their death, which Christian tradition calls in Latin "dies natalis", meaning the day of birth into the Kingdom. For all the deceased, whether Christian, Muslim, Buddhist or of other faiths, this is their dies natalis, as we repeat in Holy Mass: "Remember all those who have left this world and whose righteousness you know; welcome them into your Kingdom, where we hope to be filled with your glory together for eternity" (Eucharistic Prayer III). The liturgy refuses to use the popular expression 'day of the dead', since this day opens onto divine life. The Church calls it: Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed. 'Dead' and 'departed' are not synonyms: the term 'departed' comes from the Latin functus, which means 'he who has accomplished', 'he who has completed'. The deceased is therefore "he who has brought to completion the life" received from God. This liturgical feast is both a day of remembrance and intercession: we remember the deceased and pray for them. In the light of the solemnity of All Saints' Day, this day offers Christians an opportunity to renew and live the hope of eternal life, the gift of Christ's resurrection. For this reason, during these celebrations, many people visit cemeteries to honour their deceased loved ones and decorate their graves with flowers. We think of all those who have left us, but whom we have not forgotten. We pray for them because, according to the Christian faith, they need purification in order to be fully with God. Our prayer can help them on this path of purification, by virtue of what is called the 'communion of saints', a communion of life that exists between us and those who have gone before us: in Christ there is a real bond and solidarity between the living and the dead.

2. A little history. In order for the feast of All Saints (established in France in 835) to retain its proper character, and so that it would not become a day dedicated to the dead, St Odilon, abbot of Cluny, around the year 1000, imposed on all his monasteries the commemoration of the dead through a solemn Mass on 2 November. This day was not called a 'day of prayer for the dead', but a 'commemoration of the dead'. At that time, the doctrine of purgatory had not yet been clearly formulated (it would only be so towards the end of the 12th century): it was mainly a matter of remembering the dead rather than praying for them. In the 15th century, the Dominicans in Spain introduced the practice of celebrating three Masses on this day. Pope Benedict XV (+1922) then extended to the whole Church the possibility of celebrating three Masses on 2 November, inviting people to pray in particular for the victims of war. On the occasion of the millennium of the institution of the Commemoration of the Faithful Departed (13 September 1998), St John Paul II wrote: "In fact, on the day after the feast of All Saints, when the Church joyfully celebrates the communion of saints and the salvation of mankind, St. Odilon wanted to exhort his monks to pray in a special way for the dead, thus contributing mysteriously to their entry into bliss. From the Abbey of Cluny, this practice gradually spread, becoming a solemn celebration in suffrage of the dead, which St Odilon called the Feast of the Dead, now universally observed throughout the Church." "In praying for the dead, the Church first of all contemplates the mystery of Christ's Resurrection, who through his Cross gives us salvation and eternal life. With St Odilon, we can repeat: 'The Cross is my refuge, the Cross is my way and my life... The Cross is my invincible weapon. It repels all evil and dispels darkness'. The Cross of the Lord reminds us that every life is inhabited by the light of Easter: no situation is lost, because Christ has conquered death and opens the way to true life for us. "Redemption is accomplished through the sacrifice of Christ, through which man is freed from sin and reconciled with God" (Tertio millennio adveniente, n. 7). "While waiting for death to be definitively conquered, some men "continue their pilgrimage on earth; others, after having ended their lives, are still being purified; and still others finally enjoy the glory of heaven and contemplate the Trinity in full light" (Lumen Gentium, n. 49). United with the merits of the saints, our fraternal prayer comes to the aid of those who are still awaiting the beatific vision. Intercession for the dead is an act of fraternal charity, proper to the one family of God, through which "we respond to the deepest vocation of the Church" (Lumen Gentium, n. 51), that is, "to save souls who will love God for eternity" (St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Prayers, 6). For the souls in purgatory, the expectation of eternal joy and the encounter with the Beloved is a source of suffering, because of the punishment due to sin that keeps them away from God; but they have the certainty that, once the time of purification is over, they will meet the One they desire (Ps 42; 62). On several occasions, various popes throughout history have urged us to pray fervently for the deceased, for our family members and for all our deceased brothers and sisters, so that they may obtain remission of the punishment due to their sins and hear the voice of the Lord calling them.

3. Why this day is important: By instituting a Mass for the commemoration of the faithful departed, the Church reminds us of the place that the deceased occupy in family and social life and recognises the painful reality of mourning: the absence of a loved one is a constant wound. This celebration can also be seen as a response to the plea of the good thief who, on the cross, turned to Jesus and said: "Remember me." In remembering our deceased, we symbolically respond to that same plea: "Remember us." It is an invitation not to forget them, to continue to pray for them, keeping their memory alive and active, a sign of our hope in eternal life. Today is therefore a day for everyone: it is not only for bereaved families, but for everyone. It helps to sensitise the faithful to the mystery of death and mourning, but also to the hope and promise of eternal life. For Christians, death is not the end, but a passage. Through the trial of mourning, we understand that our earthly life is not eternal: our deceased precede us on the path to eternity. The 2nd of November thus also becomes a lesson on the 'last things' (eschatological realities), preparing us for this passage with serenity, without fear or sadness, because it is a step towards eternal life. The Church never feels exempt from prayer: it constantly intercedes for the salvation of the world, entrusting every soul to God's mercy and judgement, so that He may grant forgiveness and the peace of the Kingdom. We know well that "fulfilling life" only makes sense in fidelity to the Lord. The Church's prayer recognises our fragility and prays that none of her children will be lost. Thus, 2 November becomes a day of faith and hope, beyond the separation that marks the end of earthly life — in peace or suffering, in solitude or in family, in martyrdom or in the goodness of loving care. Death is the hour of encounter and always remains a place of struggle. The word "agony" derives from Greek and means "struggle." For Christians, death is the encounter with the Risen One, the hope in the faith professed: I believe in the resurrection of the dead and in the life of the world to come. The believer enters death with faith, rejects despair and repeats with Jesus: 'Father, into your hands I commend my spirit' (Lk 23:46). For Christians, even the hardest death is a passage into the Risen Jesus, exalted by the Father. Very often, modern Western civilisation tends to hide death: it fears it, disguises it, distances itself from it. Even in prayer, we say distractedly: Now and at the hour of our death. Yet every year, without knowing it, we pass the date that will one day be that of our death. In the past, Christian preaching often reminded us of this, although sometimes in very emphatic tones. Today, however, the fear of death seems to want to extinguish the reality of dying, which is part of every life on earth. Today's Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed is a useful opportunity to pause and reflect and, above all, to pray, renewing our fidelity to our baptism and our vocation: Together we invoke Mary, who, raised to heaven, watches over our life and our death. Mary, icon of God's goodness and sure sign of our hope, You spent your life in love and with your own assumption into Heaven you announce to us that the Lord is not the God of the dead, but of the living. Support us on our daily journey and grant that we may live in such a way that we are ready at every moment to meet the Lord of Life in the last moment of our earthly pilgrimage when, having closed our eyes to the realities of this world, they will open to the eternal vision of God.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole

Holiness: United, not separated. Deceased, not dead

XXX Sunday in Ordinary Time (year C) [26 October 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us. Another lesson on prayer from Jesus in the Gospel, and what a lesson!

First Reading from the Book of Sirach (35:15b-17, 20-22a)

'God does not judge by appearances' (Sir 35) The book of Sirach, written by Ben Sira around 180 BC in Jerusalem, was born in a time of peace and cultural openness under Greek rule. However, this apparent serenity hides a risk: contact between Jewish and Greek culture threatens the purity of the faith, and Ben Sira intends to transmit the religious heritage of Israel in its integrity. The Jewish faith, in fact, is not a theory, but an experience of covenant with the living God, discovered progressively through his works. God is not a human idea, but a surprising revelation, because 'God is God and not a man' (Hos 11:9). The central text affirms that God does not judge according to appearances: while men look at the outside, God looks at the heart. He hears the prayer of the poor, the oppressed, the orphan and the widow, and – in a wonderful image – 'the widow's tears run down God's cheeks', a sign of his mercy that vibrates with compassion. Ben Sira teaches that true prayer arises from precariousness: when man discovers himself to be poor and without support, his heart truly opens to God. Precarity and prayer are of the same family: only those who recognise their weakness pray sincerely. Finally, the sage warns that it is not outward sacrifices that please God, but a pure heart disposed to do good: What pleases the Lord above all is that we keep away from evil. The Lord is a just judge, who does not show partiality, but looks at the truth of the heart. In summary, Ben Sira reminds us that God does not judge by appearances but by the heart, that authentic prayer arises from poverty, and that divine mercy is manifested in his compassionate closeness to the little ones and the humble.

Responsorial Psalm (33/34:2-3, 16, 18, 19, 23)

Here is another alphabetical psalm, i.e., each verse follows the order of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. This indicates that true wisdom consists in trusting in God in everything, from A to Z. The text echoes the first reading from Sirach, which encouraged the Jews of the second century to maintain the purity of their faith in the face of the seductions of Greek culture. The central theme is the discovery of a God who is close to human beings, especially those who suffer: "The Lord is close to the brokenhearted." This is one of the greatest revelations of the Bible: God is not a distant or jealous being, but a Father who loves and shares in human suffering. Ben Sira poetically said that "our tears flow down God's cheeks": an image of his tender and compassionate mercy. This revelation is rooted in the journey of Israel. In the time of Moses, pagan peoples imagined rival and envious gods. Genesis corrects this view, showing that suspicion of God is a poison, symbolised by the serpent. Through the prophets, Israel gradually came to understand that God is a Father who accompanies, liberates and consoles, the 'God-with-us' (Emmanuel). The burning bush (Ex 3) is the foundation of this faith: 'I have seen the misery of my people, I have heard their cry, I know their sufferings'. Here God reveals himself as the One who sees, listens and acts. He does not remain a spectator, but inspires Moses and his children with the strength to liberate, transforming suffering into hope and commitment. The psalm reflects this experience: after undergoing trials, the people proclaim their praise: "I will bless the Lord at all times" because they have experienced a God who listens, liberates, watches over, saves and redeems. The name "YHWH," the "Lord," indicates precisely the constant presence of God alongside his people. Finally, the text teaches that in times of trial it is not only permissible but necessary to cry out to God: He is attentive to our cry and responds, not always by eliminating suffering, but by making himself present, reawakening trust, and giving us the strength to face evil. In summary, the psalm and the reflection that accompanies it give us three certainties: God is close to those who suffer and hears the cry of the poor. His presence does not take away the pain, but illuminates it and transforms it into hope. True faith comes from trust in this God who sees, hears, frees and accompanies man at all times.

Second Reading from the Second Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to Timothy (4:6-8, 16-18)

"The good fight" (2 Tim 4:6-18). The text presents St Paul's last spiritual testament, written while he was in prison in Rome, aware that he would soon be executed. The letters to Timothy, although perhaps composed or completed by a disciple, contain his authentic words of farewell, imbued with faith and serenity. Paul describes his imminent death with the Greek verb analuein, which means 'to untie the ropes', 'to weigh anchor', 'to dismantle the tent': images that evoke the departure for a new journey, the one towards eternity. Looking back, the apostle takes stock of his life using the sporting metaphor of running and fighting: "I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith." Like an athlete who never gives up, Paul has reached the finish line and knows that he will receive the "crown of righteousness," the reward promised to all the faithful. He does not boast about himself, because this crown is not a personal privilege, but a gift offered to all those who have lovingly desired the manifestation of Christ. The 'just judge', God, does not look at appearances but at the heart — as Sirach taught — and will give glory not only to Paul, but to all those who live in the hope of the Lord's coming. The apostle's life was a constant race towards the glorious manifestation of Christ, the horizon of his faith and his service. He recognises that the strength to persevere does not come from him, but from God himself: 'The Lord gave me strength, so that I might fulfil the proclamation of the gospel and all nations might hear it'. This divine strength sustained his mission, enabling him to proclaim Christ until the end. Paul explains that Christian life is not a competition, but a shared race, in which each person is called to run at their own pace, with the same ardent desire for the coming of Christ. In his letter to Titus, he defined Christians as those who “wait for the blessed hope and the appearing of the glory of our great God and Saviour Jesus Christ” — words that the liturgy repeats every day at Mass. In his hour of trial, Paul also confesses the loneliness of the apostle: The first time I made my defence, no one came to my support, but all deserted me. May it not be held against them (v. 16) . Like Jesus on the cross and Stephen at the moment of his stoning, he forgives and transforms abandonment into an experience of intimate communion with the Lord, who becomes his only strength and consolation. Paul is the poor man of whom Ben Sira speaks, the one whom God listens to and consoles, the one whose tears flow down God's cheeks. His final words reveal the hope that overcomes death: "So I was delivered from the lion's mouth. The Lord will deliver me from all evil and bring me safely into heaven, and save me in his kingdom" (vv. 17-18). He does not speak of physical deliverance - he knows that death is imminent - but of spiritual deliverance from the greatest danger: losing faith, ceasing to fight. The Lord has kept him faithful and given him perseverance until the end. For Paul, death is not defeat, but a passage to glory. It is the birth into true life, the entrance into the Kingdom where he will sing forever: 'To him be glory for ever and ever. Amen.'

In summary: The text presents Paul as a model of the believer who is faithful to the end. He experiences death as a departure towards God, not as an end. He looks at life as a race sustained by grace. He recognises that strength and perseverance come from the Lord. He understands that the reward is promised to all who desire the coming of Christ. He forgives those who abandon him and finds God's presence in solitude and weakness. He sees death as a passage into the glory of the Kingdom. Paul's "good fight" thus becomes the struggle of every Christian: to remain faithful in trials, to the point of running the last stretch with our gaze fixed on Christ, the source of strength, peace and hope.

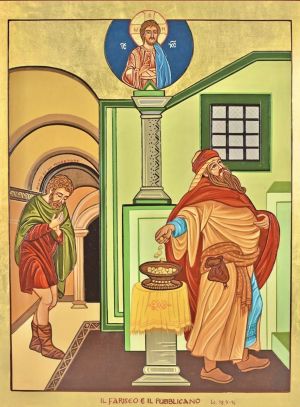

*From the Gospel according to Luke (18:9-14)

A small preliminary observation before entering into the text: Luke clearly tells us that this is a parable... so we must not imagine that all the Pharisees or all the tax collectors of Jesus' time were like those described here. No Pharisee or tax collector perfectly matched this portrait: Jesus actually presents us with two very typical and simplified inner attitudes to highlight the moral of the story. He wants us to reflect on our own attitude, because we will probably recognise ourselves now in one, now in the other, depending on the day. Let us move on to the parable: last Sunday, Luke already offered us a teaching on prayer; the parable of the widow and the unjust judge taught us to pray without ever becoming discouraged. Today, however, it is a tax collector who is offered as an example. What relationship, one might ask, can there be between a poor widow and a rich tax collector? It is certainly not the bank account that is at issue, but the disposition of the heart. The widow is poor and forced to humble herself before a judge who ignores her; the tax collector, perhaps wealthy, bears the burden of a bad reputation, which is another form of poverty. Tax collectors were unpopular, and often not without reason: they lived in a period of Roman occupation and worked in the service of the occupiers. They were considered 'collaborators'. In addition, they dealt with a sensitive issue in every age: taxes. Rome set the amount due, and the tax collectors advanced it, then received full powers to recover it from their fellow citizens... often with a large profit margin. When Zacchaeus promises Jesus to repay four times as much to those he has defrauded, the suspicion is confirmed. Therefore, when the tax collector in the parable does not dare to raise his eyes to heaven and beats his breast saying, 'O God, have mercy on me, a sinner', perhaps he is only telling the plain truth. Being true before God, recognising one's own fragility: this is true prayer. It is this sincerity that makes him 'righteous' on his return home, says Jesus. The Pharisees, on the other hand, enjoyed an excellent reputation: their scrupulous fidelity to the Law, fasting twice a week (more than the Law required!), regular almsgiving, all expressed their desire to please God. And everything the Pharisee says in his prayer is true: he invents nothing. But, in reality, he does not pray. He contemplates himself. He looks at himself with complacency: he needs nothing, asks for nothing. He takes stock of his merits — and he has many! — but God does not think in terms of merit: his love is free, and all he asks is that we trust him. Let us imagine a journalist at the exit of the Temple interviewing the two men: Sir, what did you expect from God when you entered the Temple? Yes, I expected something. And did you receive it? Yes, and even more. And you, Mr Pharisee? No, I received nothing... A moment of silence, then he adds: But I didn't expect anything, after all. The concluding sentence of the parable sums it all up: "Whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted." Jesus does not want to present God as a moral accountant who distributes rewards and punishments. He states a profound truth: those who exalt themselves, that is, those who believe themselves to be greater than they are, like the Pharisee, close their hearts and look down on others. But those who believe themselves to be superior lose the richness of others and isolate themselves from God, who never forces the door of the heart. We remain as we were, with our human 'righteousness', so different from the divine. On the contrary, those who humble themselves, who recognise themselves as small and poor, see superiority in others and can draw on their wealth. As St Paul says: 'Consider others superior to yourselves.' And this is true: every person we meet has something we do not have. This perspective opens the heart and allows God to fill us with his gift. It is not a question of an inferiority complex, but of the truth of the heart. It is precisely when we recognise that we are not 'brilliant' that the great adventure with God can begin. Ultimately, this parable is a magnificent illustration of the first beatitude: 'Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven'.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole

I-Pharisee and I-publican: God's Creative Action. Prayer of Faith, or of manner

29th Sunday in Ordinary Time (year C) [19 October 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin Mary protect us. Once again, a strong reminder of how to live our faith in every situation in life.

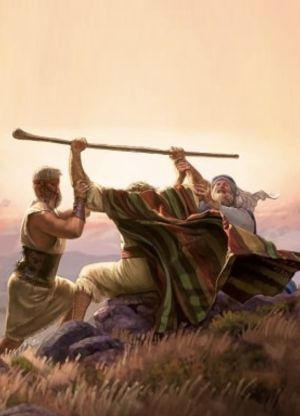

First Reading from the Book of Exodus (17:8-13)

The test of faith. On Israel's journey through the desert, the encounter with the Amalekites marks a decisive stage: it is the first battle of the people freed from Egypt, but also the first great test of their faith. The Amalekites, descendants of Esau, represent in biblical tradition the hereditary enemy, a figure of evil who tries to prevent God's people from reaching the promised land. Their sudden attack on the rear of the caravan — the weakest and most tired — reveals the logic of evil: to strike where faith falters, where fatigue and fear open the door to doubt. This episode takes place at Rephidim, the same place as Massah and Meribah, where Israel had already murmured against God because of the lack of water. There the people had experienced the trial of thirst, now they experience the trial of combat: in both cases, the temptation is the same — to think that God is no longer with them. But once again God intervenes, showing that faith is purified through struggle and that trust must remain firm even in danger. While Joshua fights in the plain, Moses climbs the mountain with God's staff in his hand — a sign of his presence and power. The story does not focus on the movements of the troops, but on Moses' gesture: his hands raised towards the sky. It is not a magical gesture: it is prayer that sustains the battle, faith that becomes strength for the whole people. When Moses' arms fall, Israel loses; when they remain raised, Israel wins. Victory therefore depends not only on the strength of weapons, but on communion with God and persevering prayer. Moses grows tired, Aaron and Hur support his hands: this is the image of spiritual brotherhood, of the community that bears the weight of faith together. Thus, prayer is not isolation, but solidarity: those who pray support others, and those who fight draw strength from the prayers of their brothers and sisters. This episode thus becomes a paradigm of spiritual life: Israel, fragile and still on its journey, learns that victory does not come from human strength, but from trust in God. Prayer, represented by Moses' raised hands, does not replace action but accompanies and transfigures it. The person who prays and the person who fights are two faces of the same believer: one fights in the world, the other intercedes before God, and both participate in the one work of salvation. Finally, the praying community becomes the living sign of God's presence at work in his people, and when a believer no longer has the strength to pray, the faith of his brothers and sisters sustains him. The story of Amalek at Rephidim is not just a page in history, but an icon of Christian life: we all live our battles knowing that victory belongs to God and that prayer is the source of all strength and the guarantee of God's presence.

Responsorial Psalm (120/121)

Psalm 120/121 belongs to the group of 'Psalms of Ascents' (Ps 120-134), composed to accompany the pilgrimages of the people of Israel to Jerusalem, the holy city situated on high, symbol of the place where God dwells among his people. The verb 'to ascend' indicates not only geographical ascent but also and above all a spiritual movement, a conversion of the heart that brings the believer closer to God. Each pilgrimage was a sign of the Covenant and an act of faith for Israel: the people, travelling from all parts of the country, renewed their trust in the Lord. When the psalm speaks in the first person — "I lift up my eyes to the mountains" — it actually gives voice to the collective "we" of all Israel, the people marching towards God. This journey is an image of the entire history of Israel, a long march in which fatigue, waiting, danger and trust are intertwined. The roads that lead to Jerusalem, in addition to being stone roads, are spiritual paths marked by trials and risks. Fatigue, loneliness, external threats — robbers, animals, scorching sun, cold nights — become symbols of the difficulties of faith. In this situation, the words of the psalm are a profession of absolute trust: "My help comes from the Lord: he made heaven and earth." These words affirm that true help comes not from human powers or mute idols, but from the living God, Creator of the universe, who never sleeps and never abandons his people. He is called "the Guardian of Israel": the one who watches over us constantly, who accompanies us, who is close to us like a shadow that protects us from the sun and the moon. The Hebrew expression "at your right hand" indicates an intimate and faithful presence, like that of an inseparable companion. The people who pray this psalm thus remember the pillar of cloud and fire that guided Israel in the desert, a sign of God who protects day and night, accompanying them on their journey and guarding their lives. Therefore, the psalmist can say: 'The Lord will guard you from all evil; he will guard your life. The Lord will guard you when you go out and when you come in, from now on and forever." The pilgrim who "goes up" to Jerusalem becomes the image of the believer who entrusts himself to God alone, renouncing idols and false securities. This movement is conversion: turning away from what is vain to turn towards the God who saves. In the New Testament, Jesus himself was able to pray this psalm as he "went up to Jerusalem" (Lk 9:51). He walks the path of Israel and of every human being, entrusting his life to the Father. The words "The Lord will guard your life" find their full fulfilment at Easter, when the pilgrim's return becomes resurrection because it is a return to new and definitive life. Thus, Psalm 121 is much more than a prayer for travel: it is the confession of faith of a people on a journey, the proclamation that God is faithful and that his presence accompanies every step of existence. In it, historical memory, theological trust and eschatological hope come together. Israel, the believer and Christ himself share the same certainty: God guards life and every ascent, even the most difficult, leads to communion with Him.

Second Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul to Timothy (3:14-4:2)

In this passage from the second letter to Timothy (3:14-4:2), Paul entrusts his disciple with the most precious legacy: fidelity to the Word of God. It is a text written at a difficult time, marked by doctrinal confusion and tensions in the community of Ephesus. Timothy is called to be a 'guardian of the Word' in the midst of a world that risks losing the truth it has received. The first words, 'Remain faithful to what you have learned', make it clear that others have abandoned the apostolic teaching: fidelity then becomes an act of spiritual resistance, a remaining anchored to the source. Paul speaks of 'dwelling' in the Word: faith is not an object to be possessed, but an environment in which to live. Timothy entered into it as a child thanks to his mother Eunice and his grandmother Lois, women of faith who passed on to him a love for the Scriptures. Here we have a reference to the communal and traditional character of faith: no one discovers the Word on their own, but always in the Church. Access to Scripture takes place within the living Tradition, that 'chain' that starts with Christ, passes through the apostles and continues in believers. 'Tradere' in Latin means 'to transmit': what is received is given. In this fidelity, Scripture is a source of living water that regenerates the believer and roots him in the truth. Paul affirms that the Holy Scriptures can instruct for the salvation that is obtained through faith in Christ Jesus (v. 15). The Old Testament is the path that leads to Christ: the entire history of Israel prepares for the fulfilment of the Paschal mystery. 'All Scripture is inspired by God': even before it became dogma, it was the deep conviction of the people of Israel, from which arose respect for the holy books kept in the synagogues. Divine inspiration does not cancel out the human word, but transfigures it, making it an instrument of the Spirit. Scripture, therefore, is not just another book, but a living presence of God that forms, educates, corrects and sanctifies: thanks to it, the man of God will be perfect, equipped for every good work (vv. 16-17). From this source springs the mission, and Paul entrusts Timothy with the decisive command: "Proclaim the Word, insist on it at the opportune and inopportune moment" (v. 4:2) because the proclamation of the Gospel is a necessity, not an optional task. The solemn reference to Christ's judgement of the living and the dead shows the gravity of apostolic responsibility. Proclaiming the Word means making present the Logos, that is, Christ himself, the living Word of the Father. It is He who communicates himself through the voice of the preacher and the life of the witness. But proclamation requires courage and patience: it is necessary to speak when it is convenient and when it is not, to admonish, correct, encourage, always with a spirit of charity and a desire to build up the community. Truth without love hurts; love without truth empties the Word. For Paul, Scripture is not only memory, but the dynamism of the Spirit. It shapes the mind and heart, forms judgement, inspires choices. Those who dwell in it become "men of God," that is, persons shaped by the Word and made capable of serving. Timothy is invited not only to guard the doctrine, but to make it a source of life for himself and for others. Thus, the Word, accepted and lived, becomes a place of encounter with Christ and a source of renewal for the Church. The apostle does not found anything of his own, but transmits what he has received; in the same way, every believer is called to become a link in this living chain, so that the Word may continue to flow in the world like water that quenches, purifies and fertilises. In summary: Scripture is the source of faith, Tradition is the river that transmits it, and proclamation is the fruit that nourishes the life of the Church. To remain in the Word means to remain in Christ; to proclaim it means to let Him act and speak through us. Only in this way does the man of God become fully formed and the community grow in truth and charity.

From the Gospel according to Luke (18:1-8)

The context of this parable is that of the 'end times': Jesus is walking towards Jerusalem, towards His Passion, death and Resurrection. The disciples perceive the tragic and mysterious epilogue, feel the need for greater faith ('Increase our faith') and are anxious to understand the coming of the Kingdom of God. The term 'Son of Man', already present in Daniel (7), indicates the one who comes on the clouds, receives universal and eternal kingship, and also represents, in the original sense, a collective being, the people of the Saints of the Most High. Jesus uses it to refer to himself, reassuring his disciples about God's ultimate victory, even in a context of imminent difficulties. The reference to judgement and the Kingdom emphasises the eschatological perspective: God will do justice to his chosen ones, the Kingdom has already begun, but it will be fully realised at the end. The parable of the persistent widow is at the heart of the message: before an unjust judge, the widow is not discouraged because her cause is just. This example combines two virtues essential to Christians: humility, recognising one's poverty (first beatitude: 'Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the Kingdom of God'), and perseverance, confident insistence in prayer and justice. The widow's persistence becomes a paradigm for faith in waiting for the Kingdom: our cause, too, based on God's will, requires tenacity. The text also recalls the connection with the episode in the Old Testament: during the battle against the Amalekites, Moses prays persistently on the hill while Joshua fights on the plain. The victory of the people depends on the presence and intervention of God, supported by Moses' persevering prayer. The parable of the widow has the same function: to remind believers, of all times, that faith is a continuous struggle, a test of endurance in the face of difficulties, opposition and doubts. Jesus' concluding question, "When the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth?", is a universal warning: faith should never be taken for granted; it must be guarded, nurtured and protected. From the early morning of the Resurrection until the final coming of the Son of Man, faith is a struggle of constancy and trust, even when the Kingdom seems far away. The widow teaches us how to face the wait: humble, stubborn, confident, aware of our weakness but certain of God's justice and saving will, which never disappoints those who trust in him totally. Luke seems to be writing to a community threatened by discouragement, as suggested by the final sentence: 'When the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth?'. This phrase, while appearing pessimistic, is actually a warning to be vigilant: faith must be guarded and nurtured, not taken for granted. The text forms an inclusion: the first sentence teaches what faith is — 'We must always pray without losing heart' — and the final sentence calls for perseverance. Between the two, the example of the stubborn widow, treated unjustly but who does not give up, shows concretely how to practise this faith. The overall teaching is clear: faith is a constant commitment, an active resistance, which requires stubbornness, humility and trust in God's justice, even in the face of difficulties and the apparent absence of a response.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole

Familiarity at the human level makes it difficult to go beyond this in order to be open to the divine dimension. That this son of a carpenter was the Son of God was hard for them to believe. Jesus actually takes as an example the experience of the prophets of Israel, who in their own homeland were an object of contempt, and identifies himself with them (Pope Benedict)

La familiarità sul piano umano rende difficile andare al di là e aprirsi alla dimensione divina. Che questo Figlio di un falegname sia Figlio di Dio è difficile crederlo per loro. Gesù stesso porta come esempio l’esperienza dei profeti d’Israele, che proprio nella loro patria erano stati oggetto di disprezzo, e si identifica con essi (Papa Benedetto)

These two episodes — a healing and a resurrection — share one core: faith. The message is clear, and it can be summed up in one question: do we believe that Jesus can heal us and can raise us from the dead? The entire Gospel is written in the light of this faith: Jesus is risen, He has conquered death, and by his victory we too will rise again. This faith, which for the first Christians was sure, can tarnish and become uncertain… (Pope Francis)

These two episodes — a healing and a resurrection — share one core: faith. The message is clear, and it can be summed up in one question: do we believe that Jesus can heal us and can raise us from the dead? The entire Gospel is written in the light of this faith: Jesus is risen, He has conquered death, and by his victory we too will rise again. This faith, which for the first Christians was sure, can tarnish and become uncertain… (Pope Francis)

The ability to be amazed at things around us promotes religious experience and makes the encounter with the Lord more fruitful. On the contrary, the inability to marvel makes us indifferent and widens the gap between the journey of faith and daily life (Pope Francis)

La capacità di stupirsi delle cose che ci circondano favorisce l’esperienza religiosa e rende fecondo l’incontro con il Signore. Al contrario, l’incapacità di stupirci rende indifferenti e allarga le distanze tra il cammino di fede e la vita di ogni giorno (Papa Francesco)

An ancient hermit says: “The Beatitudes are gifts of God and we must say a great ‘thank you’ to him for them and for the rewards that derive from them, namely the Kingdom of God in the century to come and consolation here; the fullness of every good and mercy on God’s part … once we have become images of Christ on earth” (Peter of Damascus) [Pope Benedict]

Afferma un antico eremita: «Le Beatitudini sono doni di Dio, e dobbiamo rendergli grandi grazie per esse e per le ricompense che ne derivano, cioè il Regno dei Cieli nel secolo futuro, la consolazione qui, la pienezza di ogni bene e misericordia da parte di Dio … una volta che si sia divenuti immagine del Cristo sulla terra» (Pietro di Damasco) [Papa Benedetto]

And quite often we too, beaten by the trials of life, have cried out to the Lord: “Why do you remain silent and do nothing for me?”. Especially when it seems we are sinking, because love or the project in which we had laid great hopes disappears (Pope Francis)

E tante volte anche noi, assaliti dalle prove della vita, abbiamo gridato al Signore: “Perché resti in silenzio e non fai nulla per me?”. Soprattutto quando ci sembra di affondare, perché l’amore o il progetto nel quale avevamo riposto grandi speranze svanisce (Papa Francesco)

The Kingdom of God grows here on earth, in the history of humanity, by virtue of an initial sowing, that is, of a foundation, which comes from God, and of a mysterious work of God himself (John Paul II)

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.