15th Sunday in Ordinary Time (year C) [13 July 2025]

May God bless us and the Virgin Mary protect us. Let us live this summer accompanied and guided by the Word of God.

*First Reading from the Book of Deuteronomy (30:10-14)

The Book of Deuteronomy contains Moses' last speech, a sort of spiritual testament, although it was certainly not written by Moses, since it often repeats: 'Moses said... Moses did'. The author is very solemn in recalling Moses' greatest contribution: bringing Israel out of Egypt and concluding the Covenant with God on Sinai. In this Covenant, God promises to protect his people forever, and the people promise to respect his Law, recognising it as the best guarantee of their newfound freedom. Israel makes this commitment, but it does not often prove faithful. When the Northern Kingdom, destroyed by the Assyrians, disappears from the map, the author invites the inhabitants of the Southern Kingdom, learning from this defeat, to listen to the voice of the Lord, to observe his commands and decrees written in the Torah. For they are neither difficult to understand nor to put into practice: "This commandment which I command you today is not too high for you, nor is it too far away from you" (v. 11).

A question arises: if observing the Law is not difficult, why are God's commandments not put into practice? For Moses, the reason lies in the fact that Israel is "a stiff-necked people": it provoked the Lord's anger in the desert and then rebelled against the Lord from the day it left Egypt until its arrival in the Promised Land (cf. Deut 9:6-7). The expression "stiff-necked" evokes an animal that refuses to bend its neck under the yoke, and the Covenant between God and his people was compared to a ploughing yoke. To recommend obedience to the Law, Ben Sira writes: "Put your neck under the yoke and receive instruction" (Sir 51:26). Jeremiah rebukes Israel for its infidelities to the Law: "For long you have broken my yoke and torn off my bonds" (Jer 2:20; 5:5). And Jesus: "Take my yoke upon you and learn from me... Yes, my yoke is easy and my burden light" (Mt 11:29-30). This phrase finds its roots right here in our text from Deuteronomy: "This commandment which I command you today is not too high for you, nor is it too far away from you" (v. 11). Both in Deuteronomy and in the Gospel, the positive message of the Bible emerges: the divine law is within our reach and evil is not irremediable, so that if humanity walks towards salvation, which consists in loving God and neighbour, it experiences happiness. Yet experience shows that living a life in accordance with God's plan is impossible for human beings when they rely solely on their own strength. But if this is impossible for men, everything is possible for God (cf. Mt 19:26) who, as we read in this text, transforms our 'stiff neck' and changes our heart: he 'will circumcise your heart and the heart of your descendants, so that you may love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul, and live' (Dt 30:6).. Circumcision of the heart means the adherence of our whole being to God's will, which is possible, as the prophets, especially Jeremiah and Ezekiel, note, only through God's direct intervention: "I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts. I will be their God, and they shall be my people" (Jer 31:33).

*Responsorial Psalm 18/19

Obedience to the Law is a path to the true Promised Land, and this psalm seems like a litany in honour of the Law: "the law of the Lord", "the precepts of the Lord", "the commandment of the Lord", "the judgments of the Lord". The Lord chose his people, freed them and offered them his Covenant to accompany them throughout their existence, educating them through observance of the Torah. We must not forget that, before anything else, the Jewish people experienced being freed by their God. The Law and the commandments are therefore placed in the perspective of the exodus from Egypt: they are an undertaking of liberation from all the chains that prevent man from being happy, and it is an eternal Covenant. The book of Deuteronomy insists on this point: 'Hear, O Israel, and keep and do them, for then you will find happiness' (Deut 6:3). And our psalm echoes this: 'The precepts of the Lord are upright, they are joy to the heart'. The great certainty acquired by the men of the Bible is that God wants man to be happy and offers him a very simple means to achieve this, for it is enough to listen to his Word written in the Law: "The commandment of the Lord is clear, it enlightens the eyes." The path is marked out, the commandments are like road signs indicating possible dangers, and the Law is our teacher: after all, the root of the word Torah in Hebrew means first and foremost to teach. There is no other requirement and there is no other way to be happy: "The judgments of the Lord are all just, more precious than gold, sweeter than honey." If for us, as for the psalmist, gold is a metal that is both incorruptible and precious, and therefore desirable, honey does not evoke for us what it represented for an inhabitant of Palestine. When God calls Moses and entrusts him with the mission of freeing his people, he promises him: 'I will bring you out of the misery of Egypt... to a land flowing with milk and honey' (Ex 3:17). This very ancient expression characterises abundance and sweetness. Honey, of course, is also found elsewhere, even in the desert where John the Baptist fed on locusts and wild honey (cf. Mt 3:4), but it remains a rarity, and this is precisely what makes the Promised Land so wonderful, where the presence of honey indicates the sweetness of God's action, who took the initiative to save his people, simply out of love. For this reason, from now on there will be no more talk of the onions of Egypt, but of the honey of Canaan, and Israel is certain that God will save it because, as the psalm begins, 'the law of the Lord is perfect, refreshing the soul; the testimony of the Lord is sure, making wise the simple'.

*Second Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Colossians (1:15-20)

I will begin by paraphrasing the last sentence, which is perhaps the most difficult for us: God has decided to reconcile everything to himself through Christ, making peace for all beings on earth and in heaven through the blood of his cross (vv. 19-20). Paul here compares Christ's death to a sacrifice such as those that were habitually offered in the temple in Jerusalem. In particular, there were sacrifices called 'sacrifices of communion' or 'sacrifices of peace'. Paul knows well that those who condemned Jesus certainly did not intend to offer a sacrifice, both because human sacrifices no longer existed in Israel and because Jesus was condemned to death as a criminal and was executed outside the city of Jerusalem. Paul contemplates something unheard of here: in his grace, God has transformed the horrible passion inflicted on his Son by men into a work of peace. In other words, the human hatred that kills Christ, in a mysterious reversal wrought by divine grace, becomes an instrument of reconciliation and pacification because we finally know God as he is: God is pure love and forgiveness. This discovery can transform our hearts of stone into hearts of flesh (cf. Ezekiel), if we allow his Spirit to act in us. In this letter to the Colossians, we find the same meditation that we find in John's Gospel, inspired by the words of the prophet Zechariah: "I will pour out on the house of David and on the inhabitants of Jerusalem a spirit of grace and supplication. They will look on me, the one they have pierced... they will mourn for him bitterly' (Zechariah 12:10). When we contemplate the cross, our conversion and reconciliation can arise from this contemplation. In Christ on the cross, we contemplate man as God wanted him to be, and we discover in the pierced Jesus the righteous man par excellence, the perfect image of God. This is why Paul speaks of fullness, in the sense of fulfilment: "It pleased God to have all his fullness dwell in him". Let us now return to the beginning of the text: "Christ Jesus is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation, for in him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, the visible and the invisible... All things were created through him and for him." In Jesus we contemplate God himself; in Jesus Christ, God allows himself to be seen or, to put it another way, Jesus is the visibility of the Father: "Whoever has seen me has seen the Father," he himself says in the Gospel of John (Jn 14:9). Contemplating Christ, we contemplate man; contemplating Christ, we contemplate God. There remains one more fundamental verse: "He is also the head of the body, the Church. He is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, so that he might come to have firstness in everything" (v. 18). This is perhaps the text of the New Testament where it is stated most clearly that we are the Body of Christ, that is, he is the head of a great body of which we are the members. If elsewhere he had already said that we are all members of one body (Rom 12:4-5) and (1 Cor 12:12), here he makes it clear: "Christ is the head of the body, which is the Church" (as also in Eph 1:22; 4:15; 5:23), and it is up to us to ensure that this Body grows harmoniously.

*From the Gospel according to Luke (10:25-37)

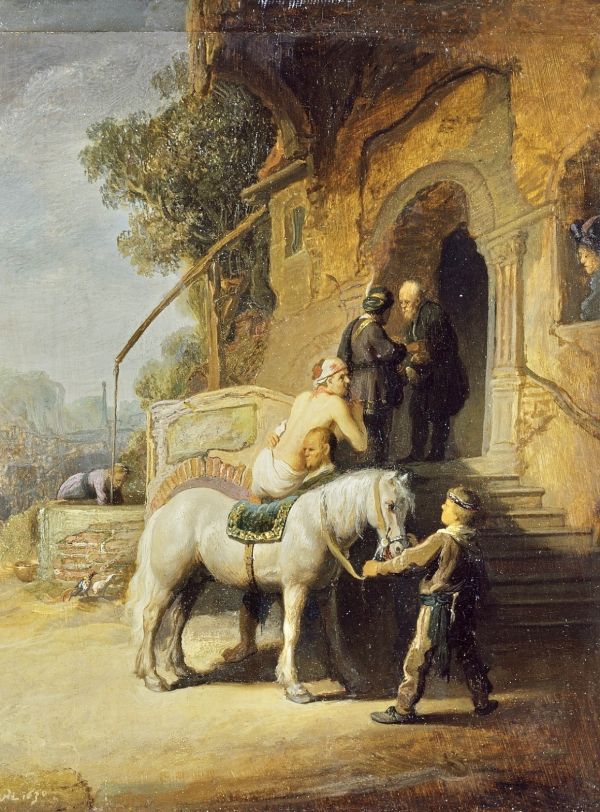

A doctor of the Law asks Jesus two challenging questions: "Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?" and, even more challenging, "Who is my neighbour?" The answer he receives is demanding. Starting from his questions, Jesus leads him to the very heart of God and places this journey in a concrete context familiar to his listeners: the thirty-kilometre road between Jerusalem and Jericho, a road in the middle of the desert, which at the time was indeed a place of ambushes, so that the story of the assault and the care of the wounded man sounded extremely plausible. A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho and fell into the hands of robbers, who robbed him and left him half dead. Added to his physical and moral misfortune is religious exclusion because, having been touched by 'unclean' people, he himself becomes unclean. This is the reason for the apparent indifference, indeed repulsion, of the priest and the Levite, who are concerned with preserving their ritual integrity. A Samaritan, on the other hand, has no such scruples. This scene on the side of the road expresses in images what Jesus himself did so many times when he healed even on the Sabbath, when he bent down to lepers, when he welcomed sinners, quoting the prophet Hosea several times: 'I desire mercy, not sacrifice, knowledge of God rather than burnt offerings' (Hos 6:6). Jesus responds to the first question of the doctor of the Law as the rabbis would, with a question: "What is written in the Law? How do you read it?" And the interlocutor recites enthusiastically: "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength, and with all your mind, and your neighbour as yourself." "You have answered correctly," Jesus replies, because the only thing that matters for Israel is fidelity to this twofold love. The secret of this knowledge, which the entire Bible reveals to us, is that God is "merciful" (literally in Hebrew: "his bowels tremble"). It is no coincidence that Luke uses the same expression to describe Jesus' emotion at the sight of the widow of Nain carrying her only son to the cemetery (Luke 7) or to recount the Father's emotion at the return of the prodigal son (Luke 15). Even the good Samaritan, when he saw the wounded man, "had compassion on him" (he was moved in his bowels). Even though he is merciful to the Jews, he remains only a Samaritan, that is, one of the least respectable, since Jews and Samaritans were enemies: the Jews despised the Samaritans because they were heretics (an ancient contempt: in the book of Sirach, among the detestable peoples, "the foolish people who dwell in Shechem" are mentioned (Sir 50:26)), while the Samaritans did not forgive the Jews for destroying their sanctuary on Mount Gerizim (in 129 BC). Yet this despised man is declared by Jesus to be closer to God than the dignitaries and servants of the Temple, who passed by without stopping. The "compassion in the bowels" of the Samaritan — an unbeliever in the eyes of the Jews — becomes "the image of God," and Jesus proposes a reversal of perspective. When asked, "Who is my neighbour?", he does not respond with a "definition" of neighbour (the Latin word "finis," meaning "limit," is also found in the word "definition"), but makes it a matter of the heart. Pay attention to the vocabulary: the word 'neighbour' implies that there are also those who are far away. And so, to the question, 'Who then is my neighbour?', the Lord replies, 'It is up to you to decide how far you want to go to be a neighbour'. And he offers the Samaritan as an example simply because he is capable of compassion. Jesus concludes, 'Go and do likewise'. This is not mere advice. He had already said to the doctor of the Law: "Do this and you will live," and now Luke highlights the need for consistency between words and deeds: it is fine to talk like a book (as in the case of the doctor of the Law), but it is not enough, because Jesus said: "My mother and my brothers are those who hear the word of God and put it into practice" (Lk 8:21). Ultimately, Jesus challenges us to a love without boundaries!

NOTE The question "What is the greatest commandment?" also appears in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, while the parable of the Good Samaritan is unique to Luke. It is also interesting to note that this positive presentation of a Samaritan (Lk 10) immediately follows the refusal of a Samaritan village to welcome Jesus and his disciples on their way to Jerusalem (Lk 9). Jesus rejects all generalisations, and this parable ultimately highlights a question of priorities in our lives.

+Giovanni D'Ercole